Picking up where we left off in Part 1, we’ll now focus on Steps 3 through 5 of taking your current job remote:

3. Create Transparency

4. Say “No” Productively

5. Rinse And Repeat

To keep you entertained throughout the lecture, we offer a bevy of animals snapped during our travels. This guy can’t wait to learn more:

Step 3. Create Transparency

As stated previously, if you’re aiming to get a remote gig by manipulating your company, best of luck — it’s not a favorable strategy. Instead, when you’re facing an uphill battle with folks who have the power to say “no”, transparency is the best policy for most of us. And yet, transparency is a currency everyone holds but few people offer. That’s where you can capitalize.

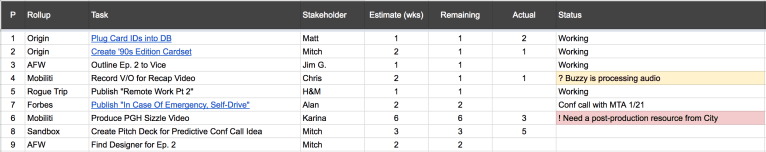

If nothing else, the one thing you should do is make your workload and progress visible to all stakeholders. Mitch has made a habit of building a shared prioritization spreadsheet that everyone from the janitor to the CEO can view. It’s not important that the CEO ever look at it — what’s important is that you’re willing to put yourself out there so you can say, “anyone at this company can see what I’m doing and how I’m doing it, at any time.” Here’s an example version using some of Mitch’s personal projects:

Design this however you like, but some of the vital components you’ll want to include in some fashion are:

- Prioritization (P): You need to show that you’re capable of focusing your effort effectively. Some popular methods to prioritization are by ascending order as shown here (1 being most important), which gives each item a distinct value. For a less strict approach, you can go High/Medium/Low or 1/2/3 and assign several tasks as “High” or “2”. Prioritization is also an imperative prerequisite for Step 4 later on in this blog.

- Task: Obviously.

- Workload: Very few people at any company know how long it should take to get something done. Giving them an idea of how many weeks a task should take and how much more time you need is extremely helpful for anyone in leadership trying to allocate resources.

- Stakeholder: If you have columns for prioritization, status and/or workload estimates, you’ll want everyone to know who’s ultimately responsible for handing you this work. This too is important for Step 4.

Anyone can do this, and should do so before proposing to free themselves from in-office direct supervision. Again, know your audience: if you were your boss or department head, what would it take to make you comfortable with an employee whose cubicle you couldn’t peek over on a daily basis?

It’s worth noting that many organizations already have processes and tools to visualize project-based work (like launching a new product), but unless you’re one of the employees whose entire job sits comfortably within those boxes, the work you’re tasked to do and the progress you’re making are often intangible… even to your boss.

It may seem like all this somehow ought to be management’s responsibility to keep track of, and that’s half correct. It’s everyone’s job to communicate and quantify the collective workload. But most of that doesn’t happen consistently, which is why managers usually fall back on the crutch of physical supervision, which is why they needlessly freak out about the idea of remote work. So yes, you are partially doing their job for your own sake.

Nice job staying with us so far… have a bison!

Transparency also extends to learning the motivations of your company. We touched on this in the last post:

- Is the company tight on cash?

- Is the company looking for innovative ways to attract and retain talent?

- Is the company struggling to improve employee satisfaction?

- Is staff size growing or shrinking significantly?

- Does local government offer the company incentives to reduce its carbon footprint?

Any of these scenarios make for good opportunities to promote telecommuting, and while you may not get straight answers from the Finance department or HR or your boss on these matters, they’re really more like rhetorical questions. You present these dilemmas and then say, “…because I think one good solution would be a remote work trial.”

Again, you’ve got to evaluate your life long before you step into this. You want to be able to lay your cards out for them, e.g. offering to take a pay cut or forgo a raise in exchange, or offering up the fact that you could be working more hours (getting rid of an hour-long commute gives you an extra working month of availability), etc. These are the easiest sells, for obvious reasons.

If you don’t want to put yourself in either of those positions, that’s okay:

- You can offer monthly check-ins with an HR/Finance committee to help them understand how you’re doing, what costs you’ve incurred, how much you’ve saved, etc. to help them benchmark the value of telecommuting to their balance sheet and to their employees

- You can start small, asking for Mondays and Fridays remote with a scheduled 90-day review

- You can even offer to be part of a task force researching the impact of telecommuting on the company

Basically, you want to make it known to your leadership that remote work is something you value, and something you’re willing to work for in order to help the company’s bottom line. That said, if this really is your last straw with your employer and you’re willing to walk away if it fails, it could be worth insisting to HR that neither your company nor any company on this planet has ample evidence that physically supervised employees are more productive or more satisfied at their jobs — and furthermore, if the company has no precedent for concern that you’ll be unproductive remotely, then what we’ve really got here is a case of potential discrimination. It’s not a route we’d recommend going down if you can avoid it, but if nothing else, you’re helping to further the cause for any potential telecommuters who will come after you. Hey, transparency is necessary, but it ain’t always the most pleasant thing.

This, however… this is the most pleasant thing.

Step 4. Say “No” Productively

So far, we’ve only talked about doing what’s necessary to get you out of the office. This next step is crucial to taking your work out on the road.

Most employees struggle with saying no — to meetings, to bosses, to additional work — for a multitude of reasons that all boil down to job security. But that’s why you have to say no productively; in doing so, you benefit from fewer time constraints weighing down your ability to go on a hike in the morning, or head out to the beach in the afternoon, or visit a friend for lunch. At its best, learning to say no will get you out of the mindset that work is one big block of time (which, by the way, is incredibly unproductive), while also helping your workforce to be more responsible.

So, how do you say no productively? This fella is all ears:

Let’s take an example:

You attend a weekly hour-long meeting with the Sales team because some executive got drunk on a plane last year and fired off an email saying “I want every department to have a pulse on the sales organization.” In that meeting, you’ve never said a word. You notice that about 10 or 11 other people have never said a word, and it’s already a 25-person meeting. Furthermore, you often go through the entire meeting without learning anything useful or relevant.

This is a meeting you need to delete from you calendar. So, instead of merely skipping out, you can continue down the path of transparency and offer up to the meeting owner that it may not be the best use of some employees’ time. Here’s a path towards saying no to this productively:

- Mention that a large number of attendees are consistently not contributing to the meeting

- Point out that the productivity cost to have those disengaged employees sitting in said meeting comes out to roughly $25k-50k per year

- Propose that the meeting owner provide an outline prior to each meeting so people know whether or not they should attend

- Go back to your department to reevaluate whether someone else would gain more from being on the call

- Alternatively, propose that an attendee of the meeting (the meeting owner would be a good choice) send out notes after the meeting’s conclusion

- At the very least, propose a survey to the attendees to find out how many of them feel the meeting is a good use of their time

You’ve just given yourself a handful of outs to delete this recurring meeting, and simultaneously given a handful of other employees the opportunity to take their time back. Remember, time is the most valuable thing, and no one in your company wants it wasted. So guard it! Guard it like this lion guards its territory!

Now, take that approach and consider everything in your calendar and inbox and task list. What do you do on a regular basis that is unproductive to your job and could easily go away, or be automated, or taken over by someone else? Move all that crap off your plate, using some of the building blocks we touched on above:

- If you don’t find it productive, it’s a waste of your time, which is a waste of the company’s resources

- If the people using up your time aren’t doing it efficiently, that’s something they’re accountable for

- There’s probably someone more junior than you (or more concerned about their job security) who will happily take over the obligation

- If it costs the company time and/or money, someone will listen to your solution

Consider also the people who take up your time: are there coworkers whose phone calls you dread because they turn a 15-minute meeting into an hour-long rant? Or whose email threads spiral out of control as they add people to the CC line? Or who always seem to sign you up for work just because you were the one gullible enough to listen? You’d be amazed how often these people’s problems magically resolve themselves if you delay responding to them, or force them to organize their information, or schedule a call rather than agreeing to hop on at their whim. Reset their expectations of communication, and hold them accountable to the time they want from you.

Don’t forget, you’ve got a completely transparent priority spreadsheet to lean on. If someone wants to know why you can’t take their call or attend a weekly meeting or tackle an additional project, just send them the link to your priorities — the workload and the people responsible for giving you that workload are right there, so if someone wants more of your time, they can take it up with the stakeholders on that sheet… which they’ll likely be afraid to do unless the work is important.

As you free up your time from these unproductive situations, where you can potentially transform your career trajectory is by investing that free time back into the company where it can actually make a mutually beneficial impact:

- Volunteer to set up knowledge transfer calls (e.g. “lunch & learns”) for other departments, where you represent your team and answer questions other departments have about what the team is working on, what challenges it faces, and how the two groups can improve on collaboration

- Find an interesting project one of your teammates (or someone in another department) is working on, and offer to help out

- Take training & education courses, both internal and external, and then distribute what you’ve learned to your teammates via a call or email

- Ask your boss if there’s any work he/she has been personally putting off which you could help bring over the finish line (this effectively makes you and your boss teammates on the same project, which goes a long way towards proving to them just how effective you can be as a telecommuter)

Doing any or all of the above exposes you and your skillset to more of the company, increases your knowledge and awareness of the company, and most importantly, paints you as someone who has the organization’s best interests in mind. Volunteering for important work while dismissing unproductive work is a virtuous cycle in that way — the more of it you do, the easier it gets, and the more people respect your approach.

Building a healthy respect for “no” at your job is a delicate balance, but it benefits every worthwhile employee when done responsibly — and all you have to do to keep it responsible is to keep it transparent.

And now… banana slug.

Step 5. Rinse And Repeat

All this effort to organize and prioritize your work, to be more transparent and assertive about your work, and to take back your time are exercises. So, like all exercise, you’ve got to keep at it.

As your transparency and organization skills improve, you’re likely to find yourself gaining more respect at work, which bodes well for your personal autonomy and ability to travel on your own schedule. And, as you hone your ability to say no productively, you’ll increase the amount of time you have for such travels, along with having a clearer head and more breathing room to have those a-ha moments of resourcefulness that are so valuable to an employer, and so inspiring as an employee.

There’s obviously a lot more to self-improvement as you develop your telecommuting career, but we’ll save that for a Part 3 sometime in the future. And, if you were looking for more tactical stuff like “how do I make sure I’ve got internet access?”, try our Day In The Life post.

The most important thing to remember? Remote work is not a perk. Everyone benefits. Society at large benefits. Go forth and transform into the free-flying butterfly you can be!